We are delighted to present a conversation between Eric Calderwood, Associate Professor of Comparative and World Literature at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and Lubna Safi, Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures at UC Berkeley. The conversation focuses on Dr. Calderwood’s second book, On Earth or in Poems: The Many Lives of al-Andalus (Harvard University Press 2023).

On Earth or in Poems tracks the varied uses of “al-Andalus” by nationalist, feminist, and aesthetic movements in the 20th and 21st centuries. In five chapters, the book explores how these movements excised, narrated, and leaned on certain aspects of al-Andalus’s memory to shape culture and politics around the world. On September 29, we spoke over Zoom and lingered on the elastic legacy of al-Andalus. Over the course of our conversation, appearing here in three parts, we discussed the central questions of On Earth or in Poems including Calderwood’s choice to center Arab and Amazigh voices, his method of “layered listening”, and this book’s relation to Colonial Al-Andalus (2018). The conversation below is edited for clarity and concision.

It should be noted that this conversation took place in late September, 2023.

LS:

I’m curious about the book’s design and the choice to go with [the Nasrid motto] la ghāliba illa Allah.

EC:

This work is a collaboration between Ms. Saffaa (@MxSaffaa) and Molly Crabapple.

My original vision for the book was to take a word that some readers might have heard of, like “al-Andalus,” and give them an image that would surprise them. My original proposal was an image by the Saudi artist Ms. Saffaa (whom I discussed at the beginning of chapter three) to suggest the idea of some of the radical politics that might be at play in the book—the idea that this is not a book about the Middle Ages, but about the contemporary moment. For a number of reasons, some having to do with rights, maybe some just having to do with sensibility, the publisher came back with a geometric design. I love that design language, but I wanted something that had a closer thematic tie to what the book was doing. Eventually we went with a shorter piece of text that was resonant with al-Andalus and that was easier to move around in a design way. So, I took the Nasrid moto from the walls of the Alhambra and that was how we ended up there. It was the press that suggested the color scheme, and I love the warmth of the orange. It could be a kind of earth tone, it could be clay, it could be sunshine.

LS:

Or the oranges in southern Spain.

EC:

It also reminded me a little bit of some of the orange tones that you get in some zalīj. I was really happy with how it came out.

LS:

You mention that you wanted to give readers a first encounter that might not immediately be recognizable as al-Andalus. Can you talk more about this idea of unfamiliar encounters with al-Andalus?

EC:

Part of this is a result of the evolution of my own thinking about al-Andalus, and part of it is the result of teaching al-Andalus at the University of Illinois. When I teach al-Andalus in my classes to undergrads, most of them immediately assume that this is something that is very distant from them in place, in time, and in culture. Very often when I’m teaching al-Andalus, or often, frankly, even when I'm talking about it in other places, I'll start by throwing up an example of the Andalusi legacy that’s actually quite close to where we are. There’s an example of this in the epilogue of the book. One of the main mosques in my area, which I noticed on my first days when I moved to Urbana, has this facade that’s designed as an homage to the Mosque of Cordoba. At the beginning of my Andalus units in class, I'll throw up that image and I'll say, how did we get here? How is it that we have this mosque that’s within blocks of our campus that’s alluding to this place that’s very distanced from us in place and time? And so that's a kind of point of entry for thinking about how there is some relationship between this deep past and the place that they're living in the present. Most of the book is about people saying—Here’s me talking about al-Andalus, and here’s what I mean about it. But I'm also interested in the ways in which we’re imbricated in the legacies of al-Andalus and how al-Andalus forms patterns around us that sometimes go unnoticed. And it’s that al-Andalus that’s woven into the fabric of everyday life that I was trying to point to in that last part of the book.

Façade of the Central Illinois Mosque and Islamic Center, Urbana. Photo by Eric Calderwood.

LS:

I am interested in how you position the reader to encounter these different al-Andaluses.

EC:

Very often when I’m encountering al-Andalus, I'm trying to figure out first of all, which al-Andalus is at work here, because very often people refer to something very specific. They'll talk about al-Andalus broadly but they're actually talking about a specific group or a specific moment and they're usually doing it for a very specific purpose: to advocate for some kind of political program, to make sense of an individual or collective experience, to coalesce around a collective identity. If I were to summarize the book in one question, it would be: What does al-Andalus do? I’ve also tried to tweak some of the tenses—thinking about al-Andalus in the subjunctive [or] in the conditional: what might al-Andalus have been, what could it be now, what might it be later. I'm trying to trouble the temporality of al-Andalus by playing with different tenses to think about the work that al-Andalus does.

LS:

Your book starts off with this problem of language, specifically you bring up convivencia, which, you say is an inadequate term, but also it’s necessary because it has a kind of purchase for the groups and for the scholarship that you're engaging with. As a concept, it does explain something about the appeal of al-Andalus. Can you talk about the problem of language?

EC:

That's a good question, and it's hard one for me to respond to it. What I meant when I described convivencia as ‘inadequate but necessary’ is in some sense related to a feeling I've had when I've gone to conferences about Andalusi studies [and heard] a paper or talk that goes something like: “Convivencia, I'm tired of that concept, let's stop talking about convivencia.” And I totally understand that instinct. The term has taken on a sort of weight and gravitational pull in conversations about al-Andalus that I don't think can be entirely ignored, even if we find it to be inadequate for describing the past. And so convivencia is one of these terms, like many terms in the book, that I take under erasure. I retain it, despite its difficulties. I study it, despite its problems and its inadequacies. I see this problem of language happening again and again whenever we try to talk about al-Andalus. How do we even define what al-Andalus is? Muslim Spain? Well, no, Spain didn’t exist yet. Muslim Iberia? But it wasn’t just Muslims. Would it be better to say Arabs? It was actually this multi-ethnic place. Immediately, we run into these terminological debates that make al-Andalus challenging to talk about. A lot of the play in the book has been about taking terms that are problematic and necessary and seeing what kind of affordances they have. Where have they been useful? For example, if we talk about Arab nationalism’s use of al-Andalus, who is excluded and who’s included?

Al-Andalus itself is a problematic term, and I tried to suggest two tools that I find helpful to working with that messiness; [those tools] were metonymy and position. Those were guiding frameworks in my book—which al-Andalus is the al-Andalus in play and from what position.

LS:

Speaking of position. You center Arab, Muslim, and Berber voices in this book. Was your previous book Colonial al-Andalus the reason that you wanted to turn to voices from the other side?

EC:

Any time you write a book and you present it to the world, very quickly you see what its shortcomings are. Colonial al-Andalus is very much a book about elites talking about al-Andalus—be they Spanish elites or Moroccan elites. It's basically [a book] about how certain powerful people on both sides of the strait of Gibraltar use al-Andalus to negotiate a certain moment in Spanish-Moroccan history. But I also wanted to think if there was a possibility to move beyond those kind of elite conversations.

[On Earth or In Poems] is a book that’s very much about al-Andalus and nationalism. We can think of nationalism being one of the ideological projects that al-Andalus has made possible, but there are other projects. Like feminism or solidarity with recent migrants to Europe. There are a lot of ideological projects that are related to the dynamics of the nation state but are not limited to it. I wanted to come up with a project that could be centered on ideological projects a little bit more than specific national spaces. Part of my desire to center Arab and Muslim voices and Arab and Muslim conversations about al-Andalus was to attempt to decenter Spanish nationalism as the privileged framework for thinking about what al-Andalus means.

LS:

I don't want to overdetermine colonialism’s role, but I can't help but think that the legacy of the colonial presence in the Middle East, not only in North Africa but even in the Levant, is the reason why al-Andalus and not the Abbasid era is elevated as the glorious past. It’s the presence of colonial powers in the Middle East and the damage they’ve done.

EC:

It probably does have something to do with al-Andalus being a celebrated site of a kind of civilizational accomplishment, and also one that is located in what is in today Europe. That’s part of it, and I think you’re absolutely right that for many writers—I'll say, particularly Levantine writers, particularly from the Syrian- Lebanese community of the late 19th and 20th century but I’ll also maybe include Egyptians—al-Andalus has served we could say a reparative role both during and after colonialism to imagine at a time of encroachment, oppression, and occupation, a time in which one’s role in the world was different.

LS:

The idea of reparative is much kinder than nostalgia or escapism.

EC:

I think nostalgia and escapism can seem dismissive and I want to take seriously the social and cultural work that kind of look to the past can do.

LS:

It’s a double-edged sword, it's repairing, but it's also wounding.

Let’s stay in the Levant and talk about Palestine. I want to talk about Darwish. His presence is palpable in the book. Can you talk about the centrality of his work and what he's done for the discourse on al-Andalus, not just for Palestine, but for our own encounters with the afterlives of al-Andalus?

EC:

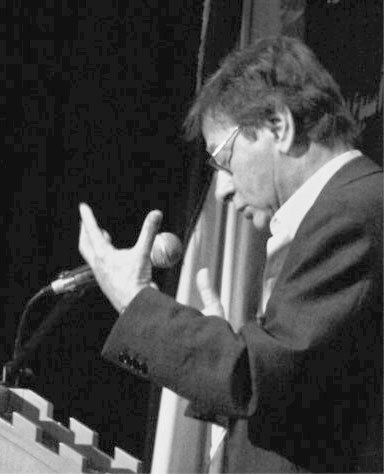

Mahmoud Darwish at Bethlehem University in 2006. Photo by Amer Shomali, CC BY-SA 3.0.

I’m so delighted to have a chance to talk about Darwish, who had such an influence on my thinking for this book, which is why I decided to borrow a line from his poetry. The title for the book, On Earth or in Poems, comes from one of Darwish's poems about al-Andalus, when he says, “And in the end, we will ask ourselves: Was al-Andalus / Here or there? On earth… or in poems?” What I understand in that line, particularly if you read it in the context of the larger poem from which it comes, is an attempt to come to terms with the fact that al-Andalus is both a place in history and a place in discourse. It's both a specific moment in the past and also a set of ideas that have transcended that specific moment and traveled to a lot of other places creating new meanings along the way. I like how it's both earth or poems because I think that that's pretty much what the book is trying to do. It's trying to work out that tension between al-Andalus as history, or earth, and al-Andalus as imagination, or poems and discourse. Both because I love that poem and because it put very concisely one of the conceptual problems of the book, that was why I drew on it [for the title].

I always knew Darwish was going to be in this book. [And] I always knew that I wanted to say something about Palestinian writings about al-Andalus. Many people who read this interview might know that Darwish wrote several famous poems about al-Andalus, and as I read those poems (and I read them a long time ago, and I've continued to come back to them in both my scholarly career and my teaching career), I had some basic questions about them: How do these poems fit into a longer tradition, or do they? I had this vague sense that al-Andalus had been a significant presence in modern Palestinian literature, but I didn't know really how deep or how long that tradition was. And crucially, I didn't know if it had evolved or varied over time. The question I had going into it, and this is hopefully moving towards a more direct answer to your question was: is the Palestinian al-Andalus always a past-oriented, nostalgia-oriented, lost-oriented paradigm? Is it Palestine was lost or occupied like al-Andalus was lost or occupied, therefore Palestine is like al-Andalus? Palestine is al-Andalus?

I didn't know how much I could do with that one way of thinking other than to acknowledge it exists. But I sensed that something much more interesting and supple was happening in Darwish’s work, and eventually in the work of several other Palestinian authors that I ended up exploring while working on that chapter. The starting point for trying to describe what that thing was, was the quote I came across in an interview Darwish did with the French newspaper Le Monde in 1983 in which he describes Palestine as “the Andalus of the possible.” I just remember coming across that quote, and my pen dropped… both because Darwish is just amazing and I always love reading Darwish, but also because I saw him signaling there a path away from a past-oriented Andalus toward an Andalus that is much more future oriented. I think he's suggesting that the power of thinking about al-Andalus resides not in what it can teach us about the past, but in what it can teach us about creating the present and even imagining possible futures.

I think you need all those times. To come back to the is versus was. Darwish is saying al-Andalus was, is, and will be at the same time, and that's the kind of complex temporality we need to think about it. And so that was a phrase that helped me land on something that I thought Darwish was doing about how to think about al-Andalus from Palestine and how to think about Palestine from al-Andalus. I also then looped that phrase back into the introduction to my book because I think it helped me put my finger on this question of time that I've been playing with, and I was trying to get out of the kind of past-present dichotomy and move to something that is a more multifaceted, multi-temporal al-Andalus in the subjunctive. Darwish plays with the subjunctive a lot in his poems. I found that to be an inviting and supple linguistic mode to think about how the memory of al-Andalus works.

LS:

That's lovely. Because it’s not just orienting al-Andalus to the present and future, you need the past, you need the it was. As you were talking right now, I was remembering the word palimpsest and so much of Southern Spain is a palimpsest, an is-wasness that’s there.

EC:

Is-wasness is a great phrase.

LS:

I take this from Solmaz Sharif who talks about a relational past tense in Farsi. I'm kind of thinking about that and how if a language has a relational past tense then you don't leave the past. Sharif talks about the American obsession with just moving on or forgetting the past and not wanting to think about it or not wanting to address it. We see this a lot today in the discussions around America’s past with slavery.

EC:

Sometimes when I've talked about this book, I've gotten questions like: talk to me about the kind of theoretical underpinnings for how you are conceiving of an Andalusi time or nostalgia or memory in this book. And those questions could lead me down a path of memory studies [or] scholarship about Benjaminian reflections on time. And all that stuff is of course part of the cultural baggage that I brought to this book. But I was actually trying to let the artists and authors themselves teach me how to think differently about time. Not to start from something outside of Darwish in order to tell me how Darwish thinks about al-Andalus but to actually see if I can work more from the bottom up and use Darwish theoretically, not only to read his own poetry, but also to think about Andalusi time outside of his poetry and outside of Palestine. The most supple theorists, if I'm going to use that word in air quotes, in this book actually ended up being poets, artists, novelists, people who are working on the border between imagination and history.

LS:

In the chapter “Harmonious Al-Andalus,” you have this approach you call “layered listening.” Whereas with previous chapters, the audience was homogenous, in this chapter, there are people in the audience who will not get certain references and some who will. How did you come to “layered listening” as a method?

EC:

I’m going to take as a starting point to answer that question the phrase you used—which was the idea that the same audience might be getting different things. Listening to these musical projects taught me that one way to get them is to get that someone else has understood them differently. I think that that’s also true of al-Andalus. We can get ourselves in the trap of trying to come up with an exclusive understanding or a correct interpretation of al-Andalus. My understanding of correct interpretations of al-Andalus starts with the premise that there are other interpretations that aren't mine, or there are other ways of understanding this thing and mine is not the exclusive one. I liked this idea of these musical projects that had a sort of multimodal understanding built into them in which people would be hearing them differently and gathering different kinds of stories from them.

The idea of layered listening was a way of coming up with a listening practice that was attuned to the different layers of history and memory that were embedded in these historical moments and was mindful about the sort of political assumptions that they might hold, while not having any one of those moments drown out the sound of the others. The way that I came to that idea was through my work on Macama jonda (1983), which was one of most famous collaborations between a Spanish flamenco artist and a Moroccan musician with a kind of Andalusi repertoire. It's a work that makes the claim that both flamenco and Andalusi music come from al-Andalus and that combining those musics in the present, in this case in 1983, both pays homage to al-Andalus and somehow revives the spirit of al-Andalus in the present at a time in which Spain was starting to experience a rise in North African migration. Yet this is also a work that draws very heavily on some of the discourses and practices of Spanish colonialism in Morocco. So there's this hidden third layer that the artists don't talk about explicitly in their framing of it, but that is very present if someone knows that history.

Still from a performance of Macama jonda (1983).

What I'm trying to do there is to figure out how to take seriously the idea that this project and the language the artists use to describe it can't exist without that colonial backstory, but [also that] its meaning can't be exhausted by that colonial backstory. “Layered listening” teaches us something about how we can reach back into the past, to the Andalusi past, even if there are layers of interference that have to be dealt with and thought about, other voices that need to be tuned into and thought about before you make the leap from the present to the medieval period. It was my way of approaching these different voices and figuring out how we can turn up the volume on some of them at different times to pay attention to what they might be doing.

LS:

You also have a playlist that goes along with this book?

EC:

It was such a joy to listen to music as I worked on this. A lot of that music (but not all of it) is available on Spotify. I would love it even if people can't read the book, if they could just listen to some of the music.

LS:

You start the book in the US with the community center that was proposed to be built a few blocks from the site of the 9/11 attacks. And you end in the US with a discussion of the Cordoba Mosque initiated by the one you see in Urbana. What is the importance of al-Andalus to the United States?

EC:

I say in the introduction that position matters when talking about al-Andalus. Position doesn't necessarily predetermine how one understands al-Andalus, but it does shape one's angle of approach—the kind of cultural baggage you bring to your first encounter with al-Andalus, your sense of proximity to it, either in place or time or culture. It felt like if I'm making the point that position matters, then failing to pay attention to my own position would be a missed opportunity. This is a book written from the United States about al-Andalus. I wanted to pay attention to the position from which this book was written without necessarily giving too much airtime to my own personal backstory with al-Andalus. One way of doing that was book-ending On Earth and in Poems with vignettes about al-Andalus in the United States.

Another claim that I make in the book is that you don't need to be near the historical site of al-Andalus to think of yourself in close connection with it. Historical proximity or geographic proximity is one way that people engage with al-Andalus, but it is certainly not the only one. I wanted to take that seriously by starting a book about al-Andalus in a place that people might not necessarily think about when they think about al Andalus—New York City —and return at the end to a place where I'm almost certain people aren't thinking about when they think about al-Andalus—Urbana, Illinois. And yet one of my contentions is that you should be. I'm not saying that the relationship between someone who lives in central Illinois is the same as someone who might have grown up in Granada or Cordoba or Fez. But it is a relationship, one that might be less visible and require different tools, but it is a relationship.

LS:

In the book you say that al-Andalus is so expansive and that you can’t really quantify it. Are there other Andaluses you wish you could have included?

EC:

When I first read Hernán Cortés’s Cartas de relación, his letters about the conquest of Mexico, it immediately struck me that he would refer to Aztec temples as mosques. And this is just one of many places you see in early Spanish chronicles in which the language to describe alterity is Muslim. And I started to think about the ways in which the European colonization of the Americas was very much built on the foundation of al-Andalus’s history, or the foundation of the history of conflicts and contact with al-Andalus—so much so that, that you have very human stories of migration, but then you have conceptual stories of migration: —[as in] how we think about what otherness is? It's like we have one slot for it, and it's like you're a church or you're a mosque. And mosque here doesn't even mean Muslim; it means “not me.” And so I wanted to think about how the Andalusi encounter had given rise to a series of conceptual categories that I think are sort of baked into the very origins of European colonization of the Americas, that first moment of violent contact.